I haven't been as diligent about writing as I'd like to be ... of course. I should have been able to predict that! At any rate, I have finished my first year of seminary, and today I begin ten weeks of CPE (clinical pastoral education) at Goodwin House, a retirement community in Falls Church, VA.

This will be a full-time gig: no sneaking home between classes to take a nap. In some ways, I imagine it will make life easier. My schedule will be pretty well dictated for me, so my priorities will be clear. But I may have to mourn the loss of that free, open schedule I had during the school year. Even at my last job I got to set my own priorities and structure my own time. This will be pretty well regimented. But we'll see ... there's a lot I don't know yet.

I am also losing my daily afternoon schedule with Sarah. We have arranged sitters for every afternoon, from the time she gets off the school bus to the time one of us gets home from work/CPE. It wasn't always easy being solo with Sarah nearly every weekday: there were lots of fights about how much homework would get done when, etc. But we did have a routine, and we'll both miss it. Things just keep shifting and changing.

I observed in my job at St. Thomas that about once a month I had to do something I had never done before. That's still the case. I think that's a pretty healthy environment in which to flourish. So here I go with some more flourishing. Please pray for me!

Monday, May 21, 2012

Saturday, May 5, 2012

God Heard It through the Grapevine

God

Heard It through the Grapevine:

An

Exegesis of Isaiah 5:1-7

by Josh Hosler

for Dr.

Fentress-Williams

Virginia

Theological Seminary

OTS-503:

Old Testament Interpretation 3

30

April 2012

From its first

notes, we recognize it as a familiar and rather hackneyed song about a

vineyard. This is surprising fare from a prophet who has gained a reputation

for gloom and doom. But the song is a guilty pleasure, and Isaiah is a good

singer, so we stop to listen. Perhaps it would have been better if we had moved

on. Isaiah’s song about a vineyard turns out to be an ever-shifting,

multi-genre suite that frustrates our expectations at every turn yet draws us

in line by line, until finally we realize that in our appreciation of the song,

we have condemned ourselves for blatant sins against God and humanity.

What kind of song is

Isaiah singing? Gene Tucker asks, “Is this really a song? If so, what kind? …

Initially, the speaker announces that he will sing a song, but when one

examines the unit as a whole, it becomes clear that the song is limited to vv.

1b-2. If it is not a song, then what is it?”[1]

Howard Wallace writes, “There has been a great deal of debate over the genre of

the passage. Suggestions have included a song, a love song, a drinking song, a

satirical polemic against fertility cults, a lawsuit, a fable, an allegory and

a parable.”[2]

We may feel it is important to identify the genre of this passage, but Brevard

Childs warns:

The problem lies in understanding the

relation between the predominately wisdom components of a parable and the

prophetic features of a judgment oracle. The very recognition of a unique

mixture of literary traditions should guard against an unfruitful search for a

formally consistent pattern with one genre. Attention to both form and function

is crucial.[3]

Isaiah has intentionally set up a

multi-genre passage that functions to keep us listening. The constant shift of

genres from verse to verse leaves us uneasy and uncertain of what to expect, so

we are caught off our guard when we finally realize that the song implicates

us. Let us imagine, then, that Isaiah began with a song that everybody knew and

then began to change it specifically in order to pull us in further. We expect

a theme, but we begin to hear variations.

| |

| Actual Hebrew text of this passage; click to enlarge |

The first lyrics

we indeed know well, for we have heard them sung often at weddings by a paid

musician or a musically inclined uncle.[4]

We can even sing along with verse 1: “I will sing now for my dear friend a song

about him and his vineyard. My dear friend has a vineyard on a fertile hill.”[5]

The lyrics are pleasant to the ear in our native Hebrew, carefully crafted to

ensure a singsong quality: “Ashirah na lididi shirat dodi. L’charmo kerem hayah lididi

b’qeren ben-shamen.” Rhyme is not a common device in our tradition, but we do

love alliteration, assonance, and plays on words. When we hear “lididi” and

“dodi,” it may as well be “do wah diddy diddy” or “da doo ron ron,” except that

these are not nonsense words: they both mean “dear” or “beloved.”  They’re fun

words to sing, and they lend themselves well to a popular but innocuous ballad.

“Ashirah” and “shirat” in English are rather like, “Sing … sing a song.”

“Kerem” and “qeren”-- the words for “vineyard” and “hill”—also sound alike.

“Qeren ben-shamen” literally means “a horn, son of oil,” but we know it in

poetic context as a “horn of plenty” or a “fertile hill.”[6]

They’re fun

words to sing, and they lend themselves well to a popular but innocuous ballad.

“Ashirah” and “shirat” in English are rather like, “Sing … sing a song.”

“Kerem” and “qeren”-- the words for “vineyard” and “hill”—also sound alike.

“Qeren ben-shamen” literally means “a horn, son of oil,” but we know it in

poetic context as a “horn of plenty” or a “fertile hill.”[6]

They’re fun

words to sing, and they lend themselves well to a popular but innocuous ballad.

“Ashirah” and “shirat” in English are rather like, “Sing … sing a song.”

“Kerem” and “qeren”-- the words for “vineyard” and “hill”—also sound alike.

“Qeren ben-shamen” literally means “a horn, son of oil,” but we know it in

poetic context as a “horn of plenty” or a “fertile hill.”[6]

They’re fun

words to sing, and they lend themselves well to a popular but innocuous ballad.

“Ashirah” and “shirat” in English are rather like, “Sing … sing a song.”

“Kerem” and “qeren”-- the words for “vineyard” and “hill”—also sound alike.

“Qeren ben-shamen” literally means “a horn, son of oil,” but we know it in

poetic context as a “horn of plenty” or a “fertile hill.”[6]

Geoffrey Grogan

writes, “The use of ‘vineyard’ or garden for a bride is often found in the Song

of Solomon … and it may have been recognized as a stock metaphor.”[7]

Yet perhaps already our suspicions are aroused due to the identity of the

speaker: this street corner scene is not a wedding, but some kind of prophetic

performance art. Carolyn Sharp suggests, “Since prophets speak for God, the

audience might suspect from the start that this male beloved is God.”[8]

Katheryn Pfisterer Darr disagrees: “Elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, the

adjective yadid often refers to

YHWH’s beloved (e.g. Israel in Jer. 11:15; Ps. 127:2, etc.; Benjamin in Deut.

33:12), although never to YHWH as ‘beloved.’ In the Song of Solomon, a young

woman frequently uses dod to refer to

the man she loves (e.g., 1:13; 2:3; 4:16; 5:10). Here, however, neither yadid or dod betrays the farmer’s identity.”[9]

Either way, it’s an intriguing situation, so we stick around to hear more.

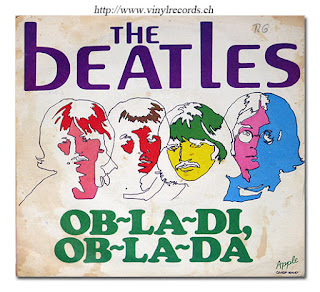

As verse 2 begins,

we might imagine Isaiah’s singsong love song to be something like the Beatles’

“Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”: the man will set up a house for his bride where the two

of them can happily get down to the work of making babies, new children of

Abraham. “And he dug around it thoroughly and de-stoned it, and he planted in

it the best possible vines.” In Hebrew this is a series of Pi’el verbs

indicating intense work: “Va-y’azqehu, va-y’saqlehu, va-yitta’ehu.” These

strong sounds change the tone and form the bridge of the song, leading toward a

familiar chorus. “And he built a tower …” Our ears prick up, for Isaiah has

departed from the familiar lyric. Let us presume there was nothing in the

original hit version about a tower. But why wouldn’t the man build a tower?

Isaiah seems to be performing his own variation on the song, and this makes it

even more interesting. Carolyn Sharp comments: “The tower will provide a dark

place for the storage of fermenting grape juice; it might also house the

vineyard owner or an employee watching over the vineyard a t night. There may be

a subtle resonance with ‘[military] watchtower’ here as well: is this

foreshadowing that sentinels will be needed to warn Israel of approaching

enemies?”[10]

Yet nothing in the song has given us a clue about where it is headed. What a

fascinating change! We do have someplace to be, but Isaiah has our attention.

Verse 2 continues: “And he built a tower in its midst, and he even hewed out a

wine-vat in it.” As Isaiah’s voice swells toward the chorus, we’re excited to

hear all about the couple’s love for each other and the birth of their

children.

t night. There may be

a subtle resonance with ‘[military] watchtower’ here as well: is this

foreshadowing that sentinels will be needed to warn Israel of approaching

enemies?”[10]

Yet nothing in the song has given us a clue about where it is headed. What a

fascinating change! We do have someplace to be, but Isaiah has our attention.

Verse 2 continues: “And he built a tower in its midst, and he even hewed out a

wine-vat in it.” As Isaiah’s voice swells toward the chorus, we’re excited to

hear all about the couple’s love for each other and the birth of their

children.

t night. There may be

a subtle resonance with ‘[military] watchtower’ here as well: is this

foreshadowing that sentinels will be needed to warn Israel of approaching

enemies?”[10]

Yet nothing in the song has given us a clue about where it is headed. What a

fascinating change! We do have someplace to be, but Isaiah has our attention.

Verse 2 continues: “And he built a tower in its midst, and he even hewed out a

wine-vat in it.” As Isaiah’s voice swells toward the chorus, we’re excited to

hear all about the couple’s love for each other and the birth of their

children.

t night. There may be

a subtle resonance with ‘[military] watchtower’ here as well: is this

foreshadowing that sentinels will be needed to warn Israel of approaching

enemies?”[10]

Yet nothing in the song has given us a clue about where it is headed. What a

fascinating change! We do have someplace to be, but Isaiah has our attention.

Verse 2 continues: “And he built a tower in its midst, and he even hewed out a

wine-vat in it.” As Isaiah’s voice swells toward the chorus, we’re excited to

hear all about the couple’s love for each other and the birth of their

children.

“And he expected a

yield of grapes … but it yielded nasty, stinking grapes.” Now there’s a shock.

This isn’t a love song at all: it’s a cheating song! Gary Roye Williams

addresses this sudden change:

The expectation of grapes (v. 2c),

perhaps a symbol of children, was fully justified, and the final word of the verse, “be’ushim,” “stinking grapes,” perhaps representing illegitimate children,

comes as a great surprise. One expects rather a synonym of “anabim,” “grapes.” The husband’s

expectations were frustrated, but so also are the interpreter’s. A major

reinterpretation of the song thus far is called for.[11]

What began as “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”

has become “I Heard It through the Grapevine”! Yet more surprises are in store.

Childs writes: “These elements of indeterminacy, which are constitutive of a

wisdom saying, function to puzzle the audience, which expects one thing but

then receives quite another, as the mood of entertainment and curiosity is

quickly dispelled by the prophet.”[12]

Even the sound of the word “be’ushim”—with a guttural aleph bursting into a “u”

vowel—banishes any singsong quality we had been enjoying.

What began as “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”

has become “I Heard It through the Grapevine”! Yet more surprises are in store.

Childs writes: “These elements of indeterminacy, which are constitutive of a

wisdom saying, function to puzzle the audience, which expects one thing but

then receives quite another, as the mood of entertainment and curiosity is

quickly dispelled by the prophet.”[12]

Even the sound of the word “be’ushim”—with a guttural aleph bursting into a “u”

vowel—banishes any singsong quality we had been enjoying.

We move into the

second section of what will turn out to be a suite, and it is here that Isaiah

changes rhythm and even vocal tone to signify that somebody different is

speaking. This is no uncle at a wedding; even the honeymoon is over. The

bridegroom himself, all worked up in grief and  anger, steps up to the

microphone in verse 3 for his recitative: “And now, residents of Jerusalem—and

man of Judah—judge, if you please, between me and my vineyard.” Isaiah has dragged us into court, and we are placed on the bench to hear the farmer’s

grievances. Verse 4 presents the formal complaint: “What more could I have done

for my vineyard that I have not already done? Why, when I expected a yield of

grapes, did it yield nasty, stinking grapes?” It is important at this point to

ask some of the same questions Joseph Blenkinsopp has asked:

anger, steps up to the

microphone in verse 3 for his recitative: “And now, residents of Jerusalem—and

man of Judah—judge, if you please, between me and my vineyard.” Isaiah has dragged us into court, and we are placed on the bench to hear the farmer’s

grievances. Verse 4 presents the formal complaint: “What more could I have done

for my vineyard that I have not already done? Why, when I expected a yield of

grapes, did it yield nasty, stinking grapes?” It is important at this point to

ask some of the same questions Joseph Blenkinsopp has asked:

anger, steps up to the

microphone in verse 3 for his recitative: “And now, residents of Jerusalem—and

man of Judah—judge, if you please, between me and my vineyard.” Isaiah has dragged us into court, and we are placed on the bench to hear the farmer’s

grievances. Verse 4 presents the formal complaint: “What more could I have done

for my vineyard that I have not already done? Why, when I expected a yield of

grapes, did it yield nasty, stinking grapes?” It is important at this point to

ask some of the same questions Joseph Blenkinsopp has asked:

anger, steps up to the

microphone in verse 3 for his recitative: “And now, residents of Jerusalem—and

man of Judah—judge, if you please, between me and my vineyard.” Isaiah has dragged us into court, and we are placed on the bench to hear the farmer’s

grievances. Verse 4 presents the formal complaint: “What more could I have done

for my vineyard that I have not already done? Why, when I expected a yield of

grapes, did it yield nasty, stinking grapes?” It is important at this point to

ask some of the same questions Joseph Blenkinsopp has asked:

There are … incongruities and problems

for the modern reader, e.g., squaring the very mundane language of the poem

with love poetry; imagining how a vineyard can be responsible for a poor crop;

why the same people represented by the failed vineyard are asked to take sides;

or, finally, why the decision to destroy is taken before those solicited have a

chance to respond by making some useful suggestions, e.g., consult an

experienced vintner, add compost, try a different kind of grape.[13]

We have already addressed the

problem of genre, and we will discover soon enough who is judging whom. But

indeed, how can a vineyard be

responsible for its own crop? Could it be that there is indeed more the farmer

could do? Did the husband do something to make his bride feel unloved? Or is

the entire metaphor about to break down? We have been sucked into this dramatic

situation, but we are given no time to review the evidence before a verdict is

pronounced in verses 5 and 6—and not by us. But by whom?

So now, listen up! I will declare to you

what I am doing to my vineyard. I will take away its hedge, and it will be

destroyed. I will break down its wall, and it will become a trampled-down

place. And I will lay it waste. It will not be pruned, and it will not be hoed,

and thorn bushes and other rough growth will come up …

The

court has become a divorce court, and this relationship is clearly over. We

move from “I Heard It through the Grapevine” into a bitter breakup song. Isaiah

is singing the part of judge, jury, and … executioner? No, for although the

farmer takes away the hedge and breaks down the wall, he does not destroy the

vineyard itself. He’s leaving, and he will allow the vineyard to be trampled by

whatever cattle come along. He will allow it to go to seed in whatever way

nature takes its course. It’s not “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia,”

but it may well be from the country genre … maybe something along the lines of

“My Give a Damn’s Busted.”

The

court has become a divorce court, and this relationship is clearly over. We

move from “I Heard It through the Grapevine” into a bitter breakup song. Isaiah

is singing the part of judge, jury, and … executioner? No, for although the

farmer takes away the hedge and breaks down the wall, he does not destroy the

vineyard itself. He’s leaving, and he will allow the vineyard to be trampled by

whatever cattle come along. He will allow it to go to seed in whatever way

nature takes its course. It’s not “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia,”

but it may well be from the country genre … maybe something along the lines of

“My Give a Damn’s Busted.” Yet in the final phrase of verse 6, Isaiah tips his

hand. The farmer will not uproot the vines, but he will make every effort to

sabotage their continued existence: “… and I will command the dark clouds not

to rain on it!” This is no farmer, and this is no husband. Only God can control

the weather.

Yet in the final phrase of verse 6, Isaiah tips his

hand. The farmer will not uproot the vines, but he will make every effort to

sabotage their continued existence: “… and I will command the dark clouds not

to rain on it!” This is no farmer, and this is no husband. Only God can control

the weather.

So now we have

come full circle. When we first noticed Isaiah on the street corner, we

expected a prophecy of doom, and we’re going to get one. We brace ourselves for

the rest of the story. We know the Assyrians are about to invade that accursed

northern kingdom of Israel, the faithless ones who worship in places other than

the temple. Surely this prophecy will be against them, we hope, as Isaiah

begins verse 7: “And the vineyard of YHWH-of-the-angel-armies is the house of

Israel.” Of course it is. We knew it all along, so we exchange self-satisfied

smirks.

“And the man of

Judah is the plantation of his delight.” With this line, Isaiah cuts us to the

bone. There we stand on the corner, tried and convicted, though we don’t even

understand yet what the charges are. All this time Isaiah has been using God’s

voice to condemn us! Gene Tucker writes:

In the middle of the parable, the

prophet, speaking as the vineyard’s ‘owner,’ directly addresses the

‘inhabitants of Jerusalem and people of Judah’ (v. 3). Finally, however, the

indictment is against the ‘house of Israel and the people of Judah’ (v. 7). For

many interpreters, the meaning of ‘Israel’ here has been a key to dating the

original address, presumed to have been delivered in Jerusalem. Eventually,

‘Israel’ came to be a comprehensive term for the chosen people, and in Isaiah

it commonly is used in more of a religious than a political or geographical

sense. If ‘Israel’ refers here to the northern kingdom, then the parable of the

vineyard probably would have originated before 722 BCE, when Samaria fell to

the Assyrians. But the historical allusions in the context are not sufficiently

specific to allow reliable conclusions.[14]

In the middle of the parable, the

prophet, speaking as the vineyard’s ‘owner,’ directly addresses the

‘inhabitants of Jerusalem and people of Judah’ (v. 3). Finally, however, the

indictment is against the ‘house of Israel and the people of Judah’ (v. 7). For

many interpreters, the meaning of ‘Israel’ here has been a key to dating the

original address, presumed to have been delivered in Jerusalem. Eventually,

‘Israel’ came to be a comprehensive term for the chosen people, and in Isaiah

it commonly is used in more of a religious than a political or geographical

sense. If ‘Israel’ refers here to the northern kingdom, then the parable of the

vineyard probably would have originated before 722 BCE, when Samaria fell to

the Assyrians. But the historical allusions in the context are not sufficiently

specific to allow reliable conclusions.[14]

We may never know

for sure, but by mentioning Israel prior to Judah, Isaiah may be employing a

funnel effect similar to that used by Amos in the first two chapters of his

book. That prophet’s condemnations move geographically like a tornado,

beginning with Damascus, circling the Jordan in a spiral, touching down in

Judah, and finally settling on Amos’s own kingdom of Israel. In this way, just

when we thought we finally knew what he was up to, Isaiah has changed genres on

us once more. This is not a love song, or a cheating song, or a breakup song,

or even a “God Bless Judah” patriotic anthem. This is a condemnation of our

nation. Gary Roye Williams gets at the heart of Isaiah’s artistic method:

The most unpleasant surprise of all is

now ready to be revealed. The phrase “men of Judah” (v. 7) creates an

expectation of antithetical parallelism. Israel was to be punished, but Judah

would be blessed (cf. Hos. i 7, xii 1). However, the parallelism is synonymous.

Suddenly the awful truth is revealed. The disappointing vineyard, the

unfaithful wife, “the house of Israel”—all refer to Judah. The Song of the

Vineyard has turned out to be a juridicial parable, by means of which the poet

has led Judah’s citizens to condemn themselves.[15]

But what have we

done to deserve this condemnation? Isaiah saves the accusation itself for the

second half of verse 7: “And he [God] expected judgment (‘mishpat’), but

behold, bloodshed (‘mishpah’)—righteousness (‘tz’daqa’), but behold, a cry of

distress (‘tz’aqa’)!” Here Isaiah uses one of the most famous examples of

wordplay in the Hebrew Bible. The words stick in our ears like the choking

sound at the center of the word “tz’aqa” sticks in Isaiah’s throat. Referring

to the oracle that follows this passage in chapter 5, Jeremy Wynne explains:

The larger context of the parable is

therefore indispensable: in their unrighteousness, the people of God have

nurtured insatiable appetites for wealth; they have hoarded property and driven

the poor from the land (5.8); they have traded the origin of their life

together, their election from among all the nations, for the pursuit of

self-indulgence and fleeting pleasures (5.11f.); and they have capitulated to

bribery and twisted the law such that it no longer protects the innocent but

rather serves as an instrument of suffering (5.23).”[16]

And now it all comes clear. The

condemnation was for both Israelite countries, even in their estrangement from

one another. The breakup lyrics tell us that we cannot assure ourselves of

God’s protection, for God intends to remove that protection and let us be

trampled down by whatever nation happens to overpower us first. Even the word

“parotz” for “break down” returns to haunt us, for it sounds rather like

“paroh” … Pharaoh! We have cheated on God, breaking our centuries-old covenant

in the way we treat each other, so God is undoing the agreement. We have

produced stinking grapes, rather than the sweet grapes that God took every

possible measure to assure and which we had no right not to produce. God loves

us and longs for us, yet what have we done in return? We stand guilty as

charged … right there on the street corner in Jerusalem, surrounded by beggars,

widows and orphans. All our expectations have been frustrated … and now we

might begin to understand how God feels about the situation. Williams notes,

“This hermeneutical frustration is a literary device which strengthens the main

message of the song: Yahweh’s frustrated expectations concerning Judah.”[17]

Is all hope lost?

Wynne reminds us that in every time and place, God’s number one purpose is

always redemption: “In righteousness, and especially in the mode of his wrath,

because God is no less free than he is loving and no less loving than free,

redemption may take a surprising route, and the yield of righteousness among

God’s people, so to speak, may finally be harvested marvelously in another

manner.”[18]

May it be so. In the meantime, we can only stand in awe at the skill of this

prophet-turned-busker who has taken our own love song, used it to draw us in,

and turned it against us to display God’s righteous judgment.

End Notes

[1] Gene M. Tucker, “The Book of Isaiah,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible, Volume VI, Leander

E. Keck et al., eds. (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2001), 87.

[2] Howard N. Wallace, “Harvesting the Vineyard: The

Development of Vineyard Imagery in the Hebrew Bible,” in Seeing Signals, Reading Signs, Mark A. O’Brien and Howard N.

Wallace, eds. (London, U.K.: T&T Clark International, 2004), 119.

[3] Brevard S. Childs, Isaiah (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 44-45.

[4] For more about Isaiah 5:1-7 as an “uncle’s song,” see

John T. Willis, “The Genre of Isaiah 5:1-7,” in Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 96, No. 3 (Sep., 1977), 337.

[5] The translation of Isaiah 5:1-7 throughout is my own.

[6] “In Isa 5:1, qeren

seems to mean hill or mountain spur (apparently, land that protrudes and is

prominent) …” Michael L. Brown, in New

International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology & Exegesis, Volume 3,

William A. VanGemeren, ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House,

1997), 991.

[7] Geoffrey W. Grogan, “Isaiah,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Tremper Longman III and David E.

Garland, eds. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008), 497.

[8] Carolyn J. Sharp, Isaiah 5:1-7, in Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised

Common Lectionary, Year A, Volume 4, David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown

Taylor, eds. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 123.

[9] Katheryn Pfisterer Darr, Isaiah 5:1-7, in Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised

Common Lectionary, Year C, Volume 3, David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown

Taylor, eds. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 343.

[10] Sharp, 125.

[11] Gary Roye Williams, “Frustrated Expectations in

Isaiah V 1-7: A Literary Interpretation,” from Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 35, Fasc. 4 (Oct. 1985), 460-461. Accessed

April 13, 2012.

[12] Childs, 45.

[13] Joseph Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1-39 (New York: The Anchor Bible Doubleday, 2000), 206.

[14] Tucker, 89.

[15] Williams, 462.

[16] Jeremy J. Wynne, Wrath

among the Perfections of God’s Life (London, U.K.: T&T Clark, 2010),

126.

[17] Williams, 465.

[18] Wynne, 119.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)